I haven’t done any text analysis work before so I decided to use Voyant since that was marked as the easiest tool to use. The Voyant home page doesn’t have a lot of options to see without text, so I put in the text to The Iliad to see what the output would look like.

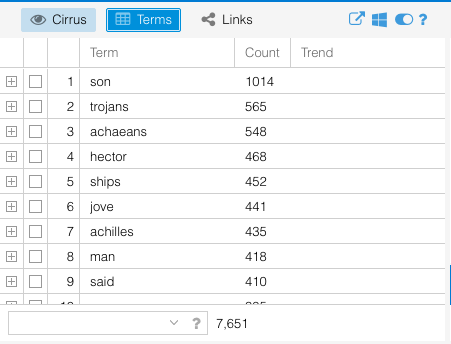

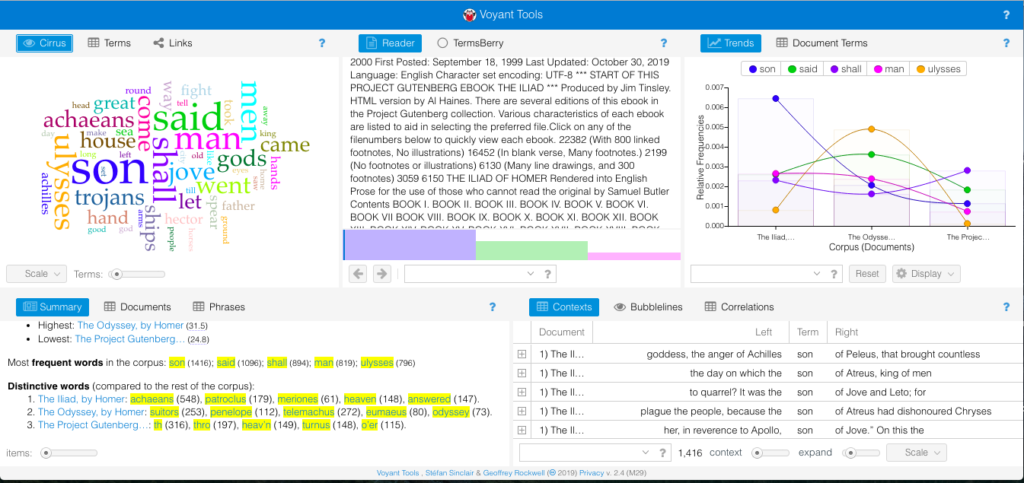

I chose The Iliad because I have read it multiple times and figured it would be a good baseline to test out what Voyant could do when I had a default skin of a corpus. I used the Voyant guide to go through the different sections at the same time that I had the The Iliad corpus open. I focused particularly on the terms list available in the Cirrus window – which also offers a nice word cloud visual – and the Trends window.

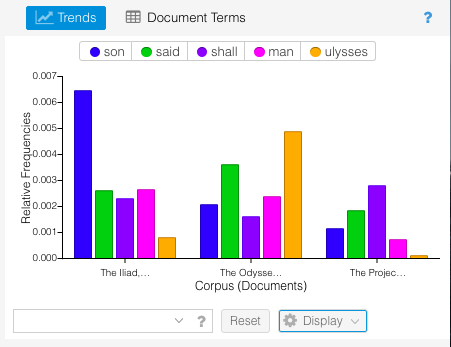

Trends view

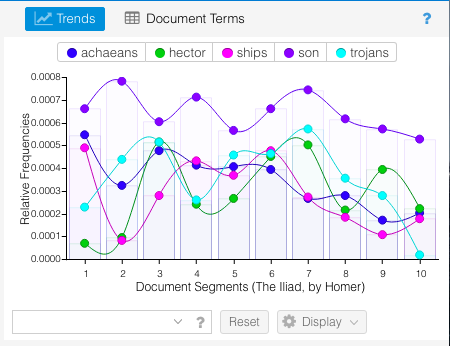

I was looking through some of the sample projects while trying to decide what to do for this project and saw one that analyzed a group of tweets from Twitter. It reminded of a New York Times article that came out a few weeks ago about NYT reporters that went through all of Donald Trump’s tweets since he became President and thought that would be an interesting experiment for this assignment. As it turns out there was an the accompanying Times Insider article that linked to a website called TrumpTwitterArchive.com (spoiler alert – they already constantly update analyses of his tweets) that also explained how they got their data.

Unfortunately, Voyant couldn’t display the data when important directly from Github – apparently JSON is still experimental – and ended up trying to analyze the source code instead of the text in the tweets.

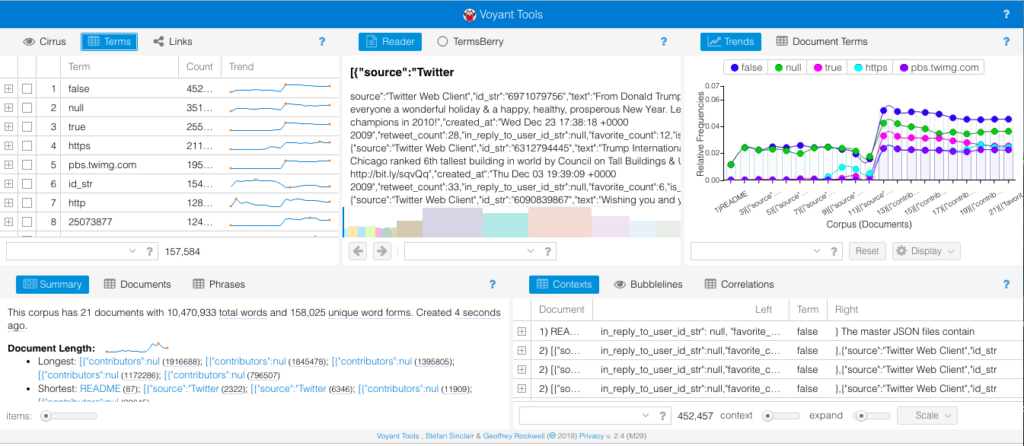

I did a search to see if anyone else had an open data set of Trump’s tweets that were in a format that Voyant could recognize but found nothing. I think this particular idea needed a tool that had more flexibility with its capabilities and user with the necessary skills and knowledge to pull it off. I still wanted to play around with a larger corpus, so I turned back to the Classics theme I had in the beginning and put in the The Iliad, The Odyssey, and The Aeneid. All of them are very well known historical epic poems written by Homer and Virgil. The default skin came out like this:

I don’t think the Summary told me anything that I didn’t already know. The Iliad and The Odyssey were both written by Homer much earlier than when Virgil wrote the The Aeneid. Given the difference in authors and time period, it makes sense that the first two epics were longer in length and had longer sentences. The Aeneid was shorter, had a higher vocabulary density, and the distinctive terms were much different than the other two (which could also be contributed to the translation). One thing I really enjoyed was the visual representations of the texts – particularly the bar graph of top words in each book.

This breakdown visually showed connections about the poems that I wouldn’t have otherwise though of. For example, “son” appeared exponentially more in The Iliad than the other two epics. This is because characters are always introduced according to their family lineage – for example “Achilles, son of Peleus.”

Since The Iliad described the events of the Trojan War, there were a larger number of characters as Heroes from many Greek cities joined the war effort against the Trojans. The introduction and description of the actions of these characters means there were many more “son of…” statements than in the other poems. Similarly, the Odyssey was the story of Odysseus’s journey home from the Trojan War, so naturally that would be the dominant word from that poem. These are connections I wouldn’t have naturally thought of when comparing the two epic poems. Overall, I can see why Voyant is the easiest text analysis tool, but I feel like this could be somewhat limiting to others who may have more coding skills and are able to utilize a wider variety of file types. Comparing these texts in this way though did visualize trends that I haven’t thought of before, and I have gone through these texts multiple times for my minor in undergrad. This exemplified what our readings noted about how distant reading doesn’t replace close reading, but creates a space where new and different questions can be asked.

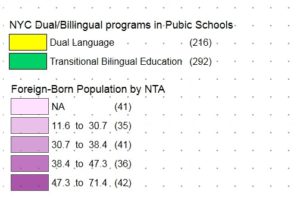

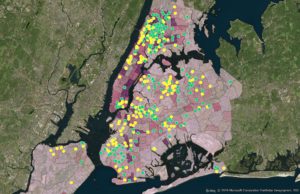

Comparing Bilingual Program Types and Foreign-Born Population by NTA

Comparing Bilingual Program Types and Foreign-Born Population by NTA