Heritage in Peril – Digital Approaches to Preservation

Institute of Fine Arts, New York University

Wednesday, October 23rd, 2019

(I apologize in advance for the long post, but I was really excited about this talk and the topic)

A few weeks ago I went to a talk held at the Instituite of Fine Arts which was promoted by Professor Gold on the MA in Digital Humanities forum. The talk, hosted by swissnex, the Swiss Consulate for Science and Technology based in Boston based on the research done at the University of Lausanne, discussed the topic of digital preservation of cultural heritage through the use of Virtual Reality. This research focused on the sites in Palmyra, Syria which were recently destroyed by ISIS in 2015 during the Syrian Civil War.

The project, known as The Collart-Palmyra Project began in 2017 “with the aim of digitizing the archives of [swiss archaeologist] Paul Collart, one of the most extensive collections of pictures, notes, and drawings from the Temple of Baalshamîn in Syria” (swissnexinnewyork.org).

A little background of the site: The Temple of Baalshamîn was dedicated to the Canaanite sky deity (possibly related to the Greek/Roman god Zeus/Jupiter). The temple’s earliest phase dates to the late 2nd century BC and has been expanded upon and rebuilt over time. In 1980, UNESCO designated the temple as a World Heritage Site (Temple of Baalshamîn, Wiki).

During the main keynote presentation by Patrick Michel of the University of Lausanne, he discussed the benefits of having digital archaeological archives. Michel mentions that digital archaeological archives can help keep objects from being stolen, moved or sold in the black market. This is due to the fact that objects can be easily searched, which will minimize or deter the amount of goods that are stolen and sold on the black market. This is an important point for archaeological finds because most of the history about an object comes from the context in which it is found. Once the object is removed from its original location (if not properly recorded) that information is forever lost.

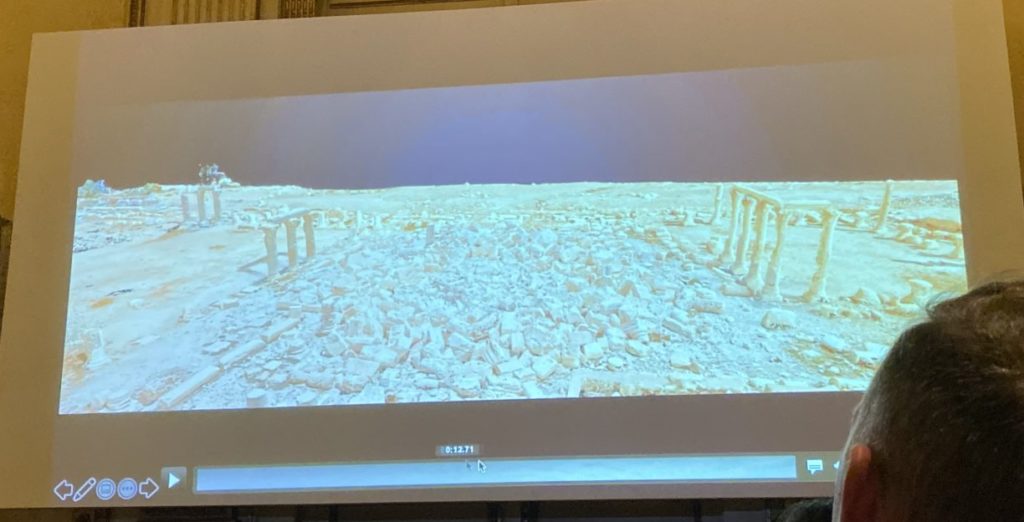

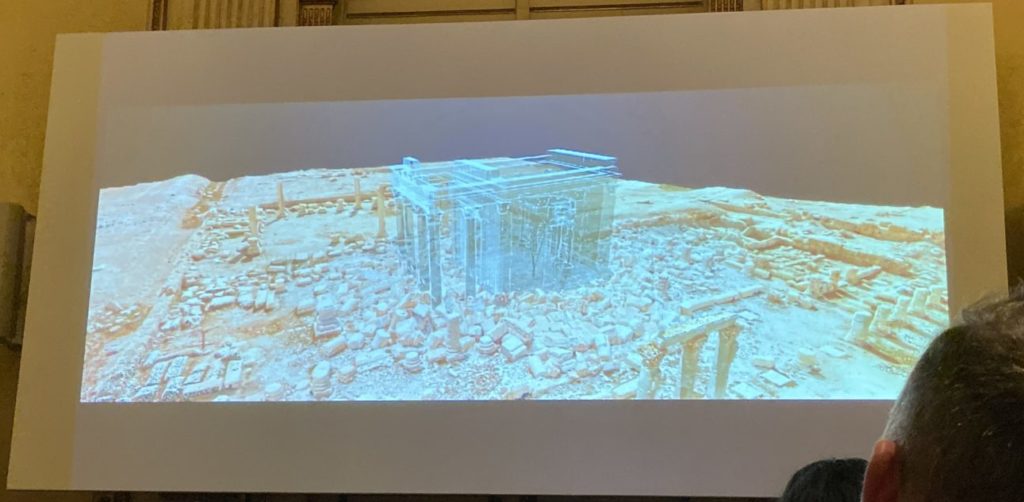

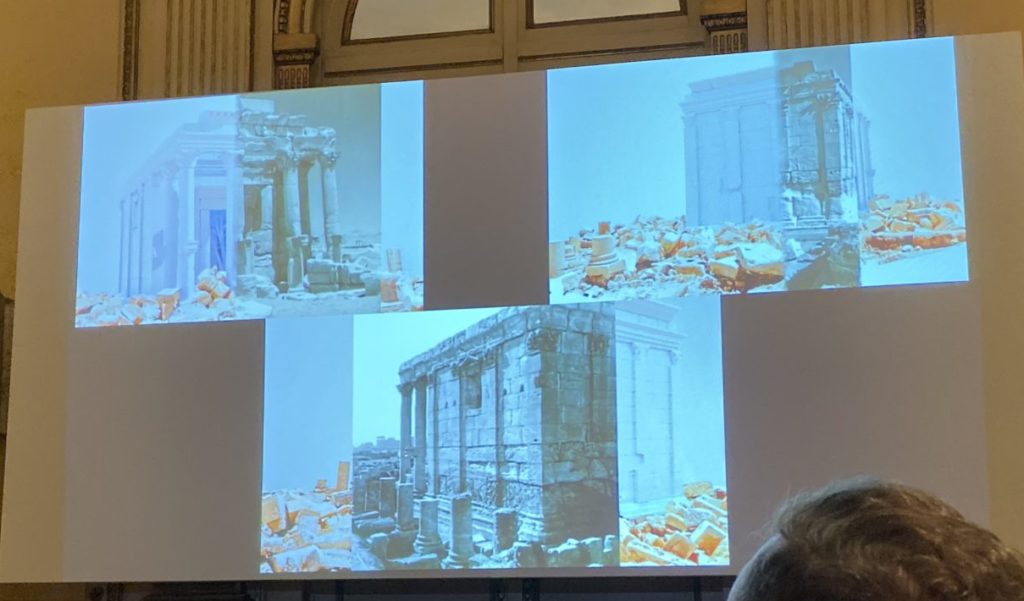

The digital reconstruction was created through the combination of photographs originally taken by Collart. These photos were held in the TIRESIAS database created in 2005-2006 by Michel (MIT Libraries). When discussing the creation of the digital reconstruction of the Palmyra site, Michel explained how they worked with multiple digital modes in order to keep track and record of the different iterations of the Temple through time. This topic came up in the discussion where someone asked if the digital reconstruction would be used to help reconstruct the site. Michel responded that, although it can be used to help with reconstruction, the question arises as to if it should be reconstructed? And if so, which iteration would be used as the basis for the reconstruction? The beauty of the digital reconstruction is that it allows for views of all iterations during the temple’s lifetime. Before the site was destroyed by ISIS, the site had some reconstruction work done, but it was based on the last iteration of the temple as that was the reality of the last time period. Now that all of the site is destroyed, what would the reconstruction be based on?

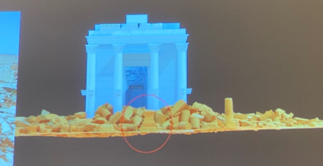

In addition to showing multiple time periods, Michel discussed how they decided to keep key identifying features that are still at the site in order to be able to match up with the digital reconstruction. An example of this can be seen to the left where the digital reconstruction aligns with a base of a column that is still in the same place now as it was before the temple was destroyed. If they were to use a VR overlay at the physical location, the digital reconstruction of the temple would be in the exact same spot as the original was, with the help of the markers.

Michel also discussed the fact that there is currently a traveling exhibit surrounding this topic in which visitors can use VR (with the help of Ubisoft) to help raise awareness of the challenges of preserving sensitive sites.

He also discussed that, although this project was done by a French institution, this panel was published in Arabic. This allows for people to be able to learn about their own culture, as opposed to the information being closed off and possibly lost to its own people.

Michel ends the discussion with mentioning how all aspects of the project are as important separately as they are together. This goes back to the discussion of the importance of the digital archives. The archive includes pictures of every item that was found at the site. The combination of the pictures of the temple is what allowed for such detailed digital reconstructions, as seen below.

Michel also brings up the negatives of this type of work where, as the web develops, this data can become outdated and be lost. He ends with asking the question, “How can digital heritage last for decades?”

Panel:

The panel held afterwards consisted of the people listed below:

Patrick Michel – University of Lausanne

Isaac Pante – University of Lausanne

Sebastian Heath – NYU Institute for the Study of the Ancient World

Dominik Landwehr – Author and Expert of Digital Culture

Patricia Cohen – The New York Times (moderator)

I will be paraphrasing what was discussed during the panel and what really stood out to me.

- When asked if they believed in open access data, the panelists had the following things to say:

- Michel – In regards to this project, the information had to be open access because they were publicly funded.

- Heath – He was for open access data, expressing that the information belongs to human kind, this is why it should be public.

- Landwehr – Although he was also for open access, he wants it to be open to those who are able to see the data in the way it is supposed to be seen and for people to have the highest quality of the information available. This can be difficult for those who do not have access to high quality graphics or technology.

- Landwehr – If the information is not open access, then who has control over it? He brought up a story where a museum in Germany got so upset when some visitors created a digital model of the Nefertiti bust and put the data on the internet for everyone to see. Questions arose surrounding this as to who has access to the data if the museum owns the physical bust. (You can see the NY Times article here)

- Heath – In response to this, Heath discussed using the Nefertiti data in his classroom, asking his students to change the point-of-view of the statue (i.e. as a kid from below, looking through glass, etc.) He brought up the point that sometimes we are too sensitive when it comes to ancient artifacts, in the sense that we feel like we cannot manipulate the original. However, using the digital data with his class in different ways led to new ideas.

- Someone asked if they felt like the digital reconstruction could ever be compared to a physical reconstruction (worried about the reliance on digital technology as opposed to the “real deal”):

- Michel – Sometimes the replica gives you the same reaction (whether it is a physical or digital replica compared to the actual object)

- Landwehr – Every new media brings up the question of if the new media is as good as the original. Take the Ancient Greeks for example, Greek philosophers argued against the discovery of writing.

- Heath – What constitutes a real image? Even photography is a rendering of life, There is no “real” image.

- Someone brought up the idea of ethics in digital projects or computer science:

- Heath – No digital act is neutral.

I had a question that I did not get a chance to ask during the panel. I was wondering, when/who decides on what sites can be digitized? I was thinking of 1) our conversations in class surrounding the fact that western areas tend to be digitized on Google Maps more so than third-world areas due to popularity and 2) the dangers of digitizing sites that need to be protected. If a site’s location is released, and is not a protected site, it can be destroyed or looted.

Thank you for reading! Please see a few more images below from the talk: