My initial intention for the Text Analysis praxis was to try to follow the procedure recommended by Lisa Rhody in the Text Analysis course I am taking this semester, as outlined in the article “How We Do Things With words: Analyzing Text as Social and Cultural Data,” by Dong Nguyen, Maria Liakata, Simon DeDeo, Jacob Eisenstein, David Mimno, Rebekah Tromble, and Jane Winters. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1907.01468.pdf. They identify five project phases (1) identification of research questions; (2) data selection; (3) conceptualization; (4) operationalization; (5) analysis and the interpretation of results.

1. Identification of Research Questions: I realized that my research aim was not really a question, but something more like: play around with text analysis.

2. Data Selection: To select my data, I decided to work with texts that I have worked on in my biblical research. I had initially thought to work with a legal term that appears in talmudic texts. I found an open access digitized corpus of the Talmud online (at https://www.sefaria.org/), but I lacked the programming skills to access the full corpus, scrape, and search it.

So I decided to work instead with the Psalms of Solomon– a collection of 18 psalms that is dated to the 2nd century B.C.E. I am currently writing an article based on a conference paper that I presented on gender stereotypes in the Psalms of Solomon. My delivered paper was highly impressionistic, and quite basic: introducing simple premises of gender-sensitive hermeneutics to the mostly-male group of conference participants. In selecting The Psalms of Solomon for this praxis, I can pull together my prior “close reading” research on this text, with the coursework for the 3 CUNY courses I am taking this semester: our Intro course; the “Text Analysis” course, in which the focus is “feminist text analysis”; and Computational Linguistics Methods 1.

Since the Psalms of Solomon is just a single document, with 7165 words (as I learned from Voyant, below), it does not lend itself to “distant reading”. I simply hoped it could serve as a manageable test-case for playing with methods.

For the Computational Linguistics course, I will work with the Greek text. (https://www.sacred-texts.com/bib/sep/pss001.htm

For our praxis, I thought it more appropriate to work with the English translation:

http://wesley.nnu.edu/sermons-essays-books/noncanonical-literature/noncanonical-literature-ot-pseudepigrapha/the-psalms-of-solomon/

(3) Conceptualization: since my main aim was to experiment with tech tools, my starter “concept” was quite simple: to choose a tool and see what I could do with the Psalms of Solomon with this tool.

(4) operationalization: After reading Amanda’s blog post about the Iliad, (https://dhintro19.commons.gc.cuny.edu/text-analysis-lessons-and-failures/) I mustered the courage to create a word cloud of PssSol with Voyant.

https://voyant-tools.org/?corpus=a748e4c58fbb317b36e0617bf8b61404

(5) analysis and the interpretation of results.

The most frequent words make sense for a collection of prayers with a national concern, and aligns with accepted descriptions of the psalms: “lord (112); god (108); shall (73); righteous (38); israel (33)”. The word “shall” is introduced in the English translation, since Greek verbal tenses are built in to the morphology of the verbs. I was pleasantly surprised to see that the word cloud reflects more than I would have expected. Specifically, it represents the dualism that is central to this work: the psalms ask for and assert the salvation of the righteous and the punishment of the wicked. I reduced the number of terms to be shown in the word cloud, and saw the prominence of “righteous”/”righteousness”, and “mercy”, as well as “pious”, and also “sinners”, though less prominently. In an earlier publication, I wrote about “theodicy” in the Psalms of Solomon– the question of the justness of God as reflected in divine responses to righteousness and evil.

Viewing this visualization of the content of Psalms of Solomon with my prior publication in mind made me feel more comfortable about Voyant, even though it just displays the obvious.

Setting the terms bar to the top 95 words further strengthened some of my warm fuzzies for Voyant. Feeling ready to step up my game, I tried to return to Step 3, “Conceptualization.” I know I want to look at words pertaining to gender. But I find myself stuck as far as I can get with Voyant.

In the meantime, I’ve met with my Comp. Linguistics prof., and my current plan for that assignment is to seek co-occurrences for some some gendered terms: possibly, “man/men” (but this can be complicated, because sometimes “man” means male, and sometimes it means “person”, and, as is well-known, sometimes “person” sort of presumes a male person to some exgent); “women“, “sons” (again, gender-ambiguous), “daughters“; maybe verbs in feminine form.

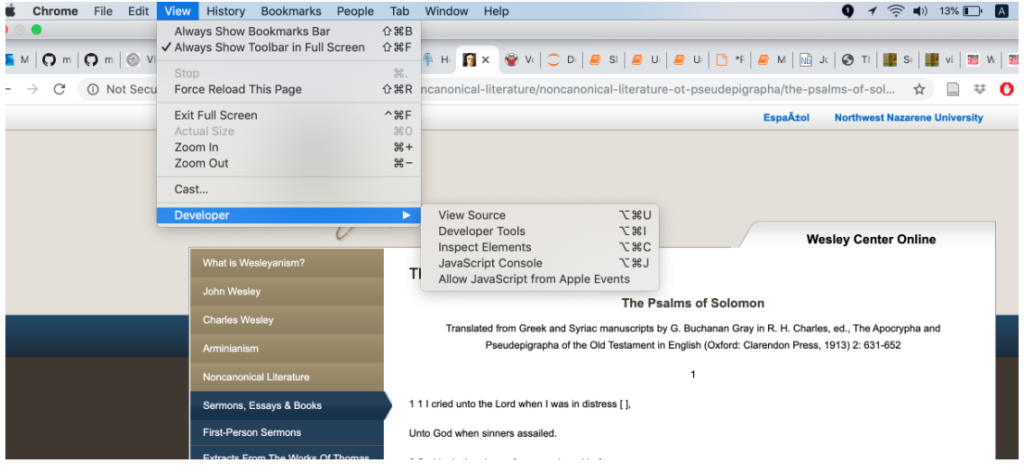

At this point, I only reached the stage of accessing the source code, which, on my machine, I do as follows:

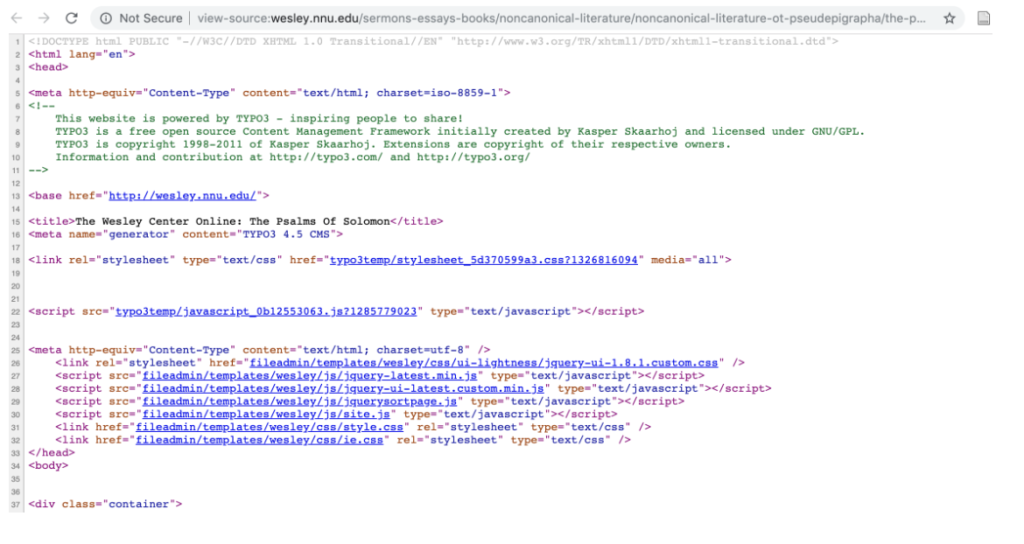

This yields:

I find this very exciting, especially the part that contains the text:

As it turns out, the code for the Greek is actually simpler than the code for the English:

I’m looking forward to working with this text, but this is as far as I’ve been able to get up to this point. My first task is to collect all of the 18 Psalms into a single file, by iterating over the URL, since the website for the Greek text has a separate page for each psalm. Then, I will think about what to search for, and how….